Half Time on the Nuffield Farming Scholarship

Half Time on the Nuffield Farming Scholarship, Written By David Tavernor, Owner of Fly2Feed

“Half time. I am now a little over halfway through my Nuffield Farming Scholarships journey studying black soldier fly production systems around the world. I have been to Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Canada, the USA, Finland, Denmark and Germany.

“Half time. I am now a little over halfway through my Nuffield Farming Scholarships journey studying black soldier fly production systems around the world. I have been to Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Canada, the USA, Finland, Denmark and Germany.

Having been in the black soldier fly world for just 2 years, my world education has been truly eye-opening. I have visited and spoken to industry leaders, be it fly breeders, larvae growers, technology engineers, politicians, scientists, humble farmers and many more. They have all given me the insights and the know-how needed to take this industry forward. I will share with you some of my findings below.

Black Soldier Fly Industry Timeline

It all started just 12 years ago with the first movers of the industry, AgriProtein in Cape Town and Enterra in Vancouver. They had this idea that you could create protein from an organic waste supply. This idea would solve world hunger simply by recycling food waste. But the real secret of this idea was that it could be done anywhere on the planet. So they raised a load of cash and built some big facilities with innovative technology.

What they didn't realise was just how difficult BSF production can be. This is factory farming like nothing before, with a species that we didn't know an awful lot about. At the time, we were lucky to have 2 scientific journals published per year! This led to more investment in knowledge and science, which meant that each company had secrets to protect. There was no collaboration between the leaders of this world.

What they didn't realise was just how difficult BSF production can be. This is factory farming like nothing before, with a species that we didn't know an awful lot about. At the time, we were lucky to have 2 scientific journals published per year! This led to more investment in knowledge and science, which meant that each company had secrets to protect. There was no collaboration between the leaders of this world.

As we got further through the 2010 decade, similar facilities started opening up, mainly in Europe and Southeast Asia, but this time, with more investment, heavier automation and even more science. All of which led to more secrecy and intellectual property. It was difficult to know what each business was doing in the industry and how much success they were having.

As this was happening, there were a lot of smaller operators developing technology and specialising in their niches. I'm talking about specialist egg breeders developing BSF genetics, microbiologists developing fermented feed technology, or controlled environment engineers developing housing hardware.

Then came the casualties. Agriprotein and Enterra went bust in the early 2020s. From what I've discovered, this was not just a result of a lack of funding. But because they tried to grow too quickly. Operating at scale is tough. There come problems with environment control, feedstock supply, logistics of where to send the frass, colony collapse, management disagreements, or investor relations. You end up becoming not just a black soldier fly company. But a waste management, logistics, engineering, feed and marketing company rolled into one. After all of this, the product still hasn't been proven to work completely yet.

There's a lesson from this: don't get too big for your boots.

And so from these infamous bankruptcies spawned new thinking in the industry. If it is too difficult to do this all in one facility, can we segment the market better?

The road to commercialisation

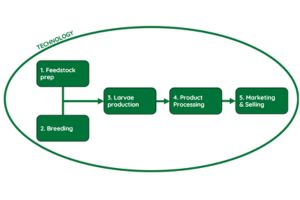

In order for the industry to compete commercially, I believe that we need to effectively segment the supply chain into the following sectors.

In order for the industry to compete commercially, I believe that we need to effectively segment the supply chain into the following sectors.

🪰 Feedstock preparation

🪰 Breeding

🪰 Larvae production

🪰 Product processing

🪰 Product Marketing

We need the right technology and government policy to optimise those 5 sub-sectors. If one link breaks, the entire chain breaks.

So far, I have seen sizeable investment in breeding and a lot of focus on both software and hardware technology. However, I haven't seen nearly enough larvae production, so those technology providers and breeders need larvae growers for them to thrive rather than survive. Similarly, you cannot process the product without scale from the larvae production. Currently, the biggest BSF factories can produce up to 40,000t per year of live larvae. Whilst this sounds like a lot, this would feed half an aquaculture farm in Norway. A drop in the ocean. This is why I think we need dedicated businesses to aggregate and process the product from multiple larvae producers.

How to focus your BSF strategy

One of the founders of a company I visited in Canada, Luis Ortiz, told me that there are two types of BSF business. One that is input-focused and one that is output-focused. The local market of operation heavily influences your business focus, as I will explain in two examples below.

One of the founders of a company I visited in Canada, Luis Ortiz, told me that there are two types of BSF business. One that is input-focused and one that is output-focused. The local market of operation heavily influences your business focus, as I will explain in two examples below.

Example 1: Luis positioned his company, Infinite Harvest Technologies, as input-focused, as there was a lot of waste fruit and grains in his area going to landfill, therefore he could command a gate fee for taking on the waste. I later found out in North America that demand for alternative protein is not quite as high when compared to Europe and this is because they produce their soy protein.

Example 2: Using my own experience of the European market, where we have successfully built biogas infrastructure, the gate fees are actually reversing so that "food waste" now has a market value. This is probably why the majority of the European businesses are output-focused, selling protein into the pet food market.

Similarly, regulation provides an important steer (or, I should say, enforced guidance) for your business focus. In Chile, I encountered a business, Food4Future, that was utilising a huge variety of feedstock, with a gate fee, because there was no regulation as to what feedstock can/cannot be used. Whereas, in Europe, there are tight regulations around what feedstock can be used. Again this shifts the focus in Europe away from the input and onto the output.

What I find frustrating in the UK is that the output is also heavily regulated because processed larvae cannot be fed to pigs or poultry and frass has to be treated heavily before fertilising plants. This heavy regulation is creating a huge cost barrier for new entrants.

I have had many creative thoughts whilst on my travels about how to find my business focus for when I return. A Nuffield Scholar from the Netherlands told me that they are having to pay €30/t to get rid of their manure, so is this a possible way to commercialise BSF in the UK? Or can the low-cost method of live larvae feeding also work?

Where are the practical minds?

The more subtle observation that I've made on my travels has been regarding the personalities in the industry. There are some super smart people operating in this space, far smarter than I am and will ever be. The combined annual growth rate projections of 30%+ have perhaps attracted these people to the industry. They see a big pie being baked and they want a slice of it. Ivy league engineers, scientists, corporates wanting their next promotion, "grantrepreneurs" and city finance whizzes have flooded the market searching for their get-rich-quick-slice-of-pie.

However, common sense is not a flower that grows in every garden. There seems to be a real lack of practicality and focus on making the business profitable. What I have seen is that this pie we're baking is highly complex and needs close attention and nurturing to create a business and industry that we can all be proud of and that will make profitable revenue streams. I feel that in this industry those who aren't in it for the long haul, won't create sustainable long-lasting businesses.

What's next on my BSF tour…

I head to Africa, where I will spend a week in Cape Town, where I understand that there are scientists, policy-makers and industry working together to develop a highly functioning industry. Followed by Rwanda, Kenya and Tanzania, where there is a huge mass of BSF businesses being run at all different scales.

If you have anything you'd specifically like me to find out, leave me a comment.

Please don’t forget to give me a follow on LinkedIn where I am posting more content.”

Read our article 'Nuffield Scholars to focus on farm diversification opportunities' here.

- Log in to post comments